Woven into her DNA: The water-human health link

Meet Maronel Steyn

Since her days as a student, Maronel Steyn has held a real passion for human health issues and the connection to water. Today, she is a CSIR senior researcher with deep-seated knowledge in water epidemiology and water resources management.

“I completed all my studies in environmental health at the former Technikon Free State, now known as the Central University of Technology, Free State. My Honours degree research project focused on investigating methemoglobinemia, which affects how red blood cells deliver oxygen in the body and which can, among other things, be caused by high nitrate levels in groundwater. Its presence may be missed, even by health workers, as the blueish pigmentation would not be visible on darker skinned babies.

For her Master's degree, Steyn conducted a human health risk assessment on pathogens and some viruses found in water to determine the human health risks when using water that is not treated properly or when people do not have access to clean water. The study considered water consumption from sources such as rivers, springs, canals and so forth, as well as river water in which children swam for recreation purposes.

She is currently working towards her PhD, which focuses on uncovering the genetic impacts of acid mine drainage on human liver cancer cells. “I hope to contribute to the understanding of how humans are being impacted by the acid mine drainage in the Krugersdorp area of Johannesburg,” she says.

Adding a feminine sparkle to water research

The water sector is still male-dominated and therefore every woman’s presence therein is important for those to come.

“Women are still few and far between when it comes to water research. Women certainly add a unique and softer touch; a different angle in projects. This, however, does not mean that we need special treatment – women can stand their ground,” she says, adding, “I do think it is great that increasingly, more female scientists focus on water. Water is a key aspect of survival and we need as many people as possible to focus their energy on it.”

“Women are often the glue that keeps communities and families connected. The role of women and water in a household has been described in the literature for millennia,” she says.

“It was not planned this way, but somehow the CSIR Stellenbosch-based water team, unlike our Pretoria team, is predominantly made up of women. They are all strong women, in will and mind, and I love that. There is never a dull moment. We have so much in common and stand together when most needed.”

Even though the pandemic enforced social distancing on the team until recently, the team once again prioritise time to socialise and build teamwork as well as celebrate personal life achievements (e.g. throwing a baby shower for a colleague or sharing birthday cake for someone’s birthday during tea break).

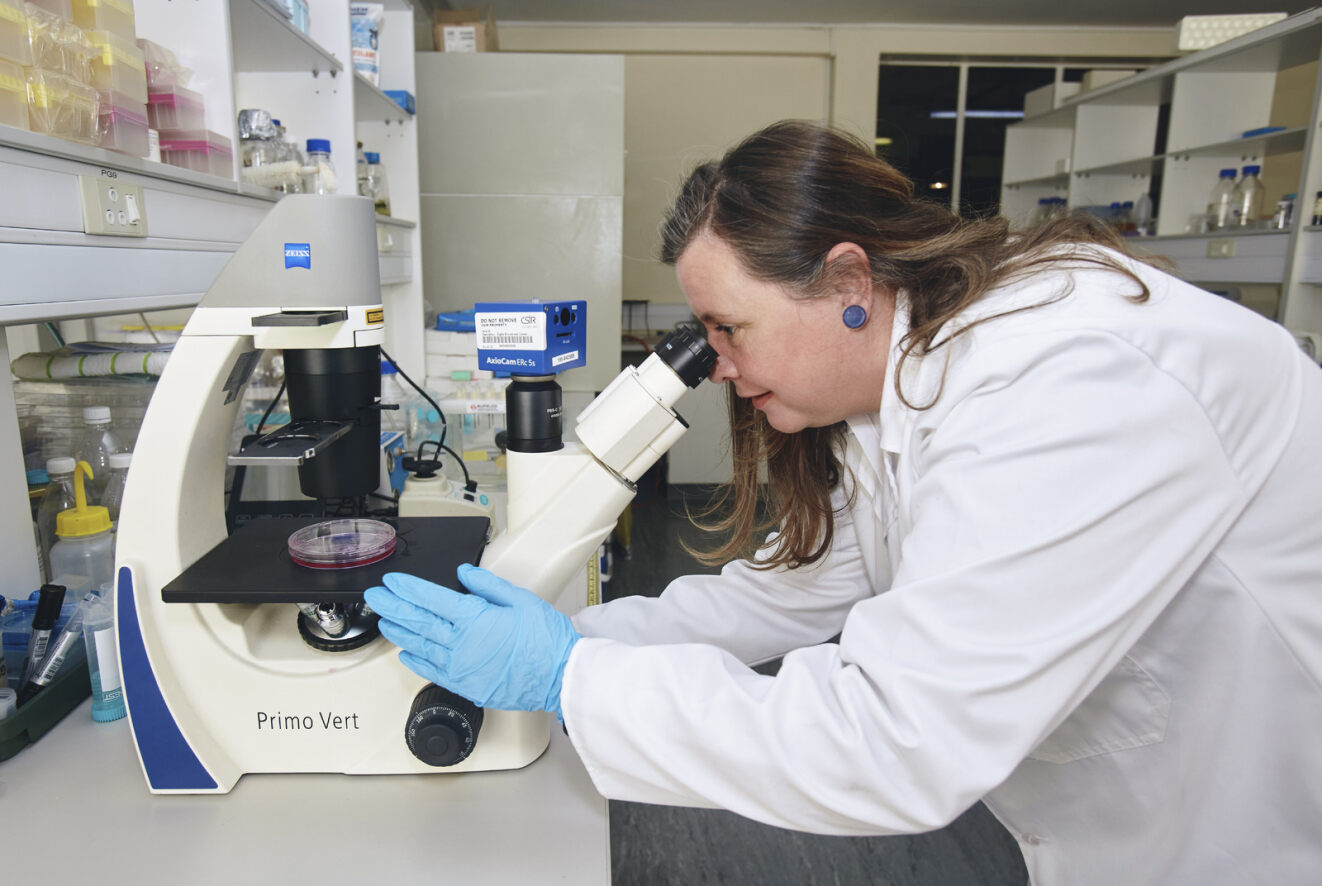

Maronel Steyn uses a biological treatment method to apply in the treatment of wastewater.

Steyn acknowledges the efforts of many to support women in science, engineering and technology, but believes that more can be done.

“In our country, there is little effort to assist women to obtain their degrees or encourage shared responsibility to achieve a work-life balance, raise children and run households. As women, we tend to be hard on ourselves because we have so many responsibilities. But the balance depends on us. We tend to be harder on ourselves than those around us. As women, we need to be cognisant of the fact that we need balance and we should also stop making ourselves feel guilty when we yearn for work-life balance.”

“As I grow older, things are different. Before I started a family with my husband, he was aware that I was very determined to achieve my career goals. However, things change as life changes – priorities change too. And this is why I mention work-life balance because it is reflective of what stage you are in life and the necessary decisions and priorities you need to make. In the end, hopefully, you would have made a difference in what matters.”

Not an obvious career choice

Steyn says that there are gaps in water research but that the opportunities in the field are not always clear and often do not receive the same exposure as more mainstream professions at career days. “I have participated in many career and science fairs, demonstrating initiatives that illustrate the importance of water, such as handwashing campaigns. Yet, this does not necessarily inspire someone to embark on a career in water research – it is far more attractive to become a medical doctor or a lawyer than a researcher,” she explains.

“There is no direct study path to becoming a water researcher. As a civil engineer, you can work on water projects and even as a marine biologist it is clear that you’ll be interacting with water. The path towards becoming a water researcher may come from doing a water quality research course, biosciences or environmental health, meaning you indirectly qualify as a water researcher,” she says.

Understanding the importance of the water-human health link

A few years ago when the Western Cape experienced a crucial low in its dam water levels, a concerted effort was made to avoid reaching ‘Day Zero’. This served as a valuable lesson that access to quality water is a privilege. Increased information and knowledge need to be shared with the public on the importance of how water and health are interconnected. Authorities and the public need to take care of the water situation in the country, and not only when we are facing an outbreak or a water crisis.

A meaningful contribution

Reminiscing on the first project she worked on when she joined the CSIR, “It focused on addressing the rat-tailed (Eristalis tenax (Linnaeus)) maggots that infested the water in Cape Town,” she says.

Over the years she has been involved in several projects and currently phycoremediation is the focus of her work. “Phyco” means algae and remediation refers to treatment – it describes a biological treatment method for the treatment of wastewater. The micro algae are sourced from nature. This initiative is impactful in that a water-scarce South Africa needs to reuse more and more water and the technology employed not only allows the reuse of more wastewater, but it is a low-cost treatment that could be applied to different types of wastewaters. Phycoremediation allows for the removal of various pollutants such as nutrients and metals, and for closing the loop through beneficiation of the biomass for the production of fertiliser, biogas or biofuel.

The work on phycoremediation at the CSIR dates to almost four decades ago. However, at the time, there wasn’t a high appetite for it. Things have since changed and increasingly, wastewater is now seen as a resource and not waste. This also encourages innovative ways of treating it – nature-based solutions are preferred, therefore plants and algae are viable treatment options. Algae has a very fast growth and survival rate, which helps in wastewater treatment processes.

To date, the CSIR research team has been treating domestic wastewater at wastewater treatment plants where some of the systems do not make use of electricity. “We are able to keep the cost low, treat the wastewater and remove nutrients. It neatly matches the aims of the circular economy. We have implemented the technology in Malawi and we have also managed an African Development Bank project with partners from the University of the Free State for the second time with four collaborating partners – we conducted feasibility studies for Namibia, Mauritius, Mozambique and Botswana,” she says.

Essential: water workers

The world of water is an exciting and rewarding one and one that is changing significantly. “I think we are in for huge changes. Big data, artificial intelligence (AI), the use of Earth observation, drone technology and digitisation will increasingly play a big role in water management in the near future. Cities can consider doing source tracking of water-related issues with the use of AI and use technology to detect water leaks as early as possible. Sampling a river with the use of drone technology has become a reality.

Making use of diverse skills and knowledge areas in water research must be investigated, therefore areas such as citizen science and having a local champion/s in a project can go a long way in working with communities.

I work with people, I love working with communities and it is important for me to do so,” she concludes.

at the CSIR Microbial Laboratory in Stellenbosch.